Chaos in Art and Cultural Practice Part 1: How Math Affects Art and Perception.

For some it may be difficult to imagine how developments in mathematics have affected the evolution of the arts and the course of culture, let alone how they may change our own practice and how we contextualize our work. What does Math have to do with Art.

A brief look at history reveals a picture of a deep underlying relationship between the inspirations and aspirations of mathematicians and artists.

The Greeks thought the nature of numbers and the universe was to be found in ratios. Pythagoras1 saw all things as relationships defined by the void between them 2, in the same way that the spaces between beats in a piece of music determine its rhythm and tempo. This is where we get our concept of “rationality”.3

The “Golden Ratio” was particularly cherished by the Greeks and can be found in a rectangle that is constructed such that removing of a square equal to its height from one end, will leave a smaller rectangle of the same proportions at the other.

Architectural historians have identified the use of this ratio in the design of the Acropolis, and so mathematicians refer to this proportion by the first letter of the name Phidias (Gr. Phi, or ), as he is credited with designing that Athenian Temple complex.

Further popularized in Luca Pacioli’s 1509 book Divina Proportione, which was illustrated by Da Vinci and includes the famous picture of the Vitruvian Man, this so-called “Golden Ratio” has been used since the Renaissance by artists as a guide to producing works with pleasing proportions. It has been seen as emblematic of the ideals of rationality. Ironically, is also an irrational number.

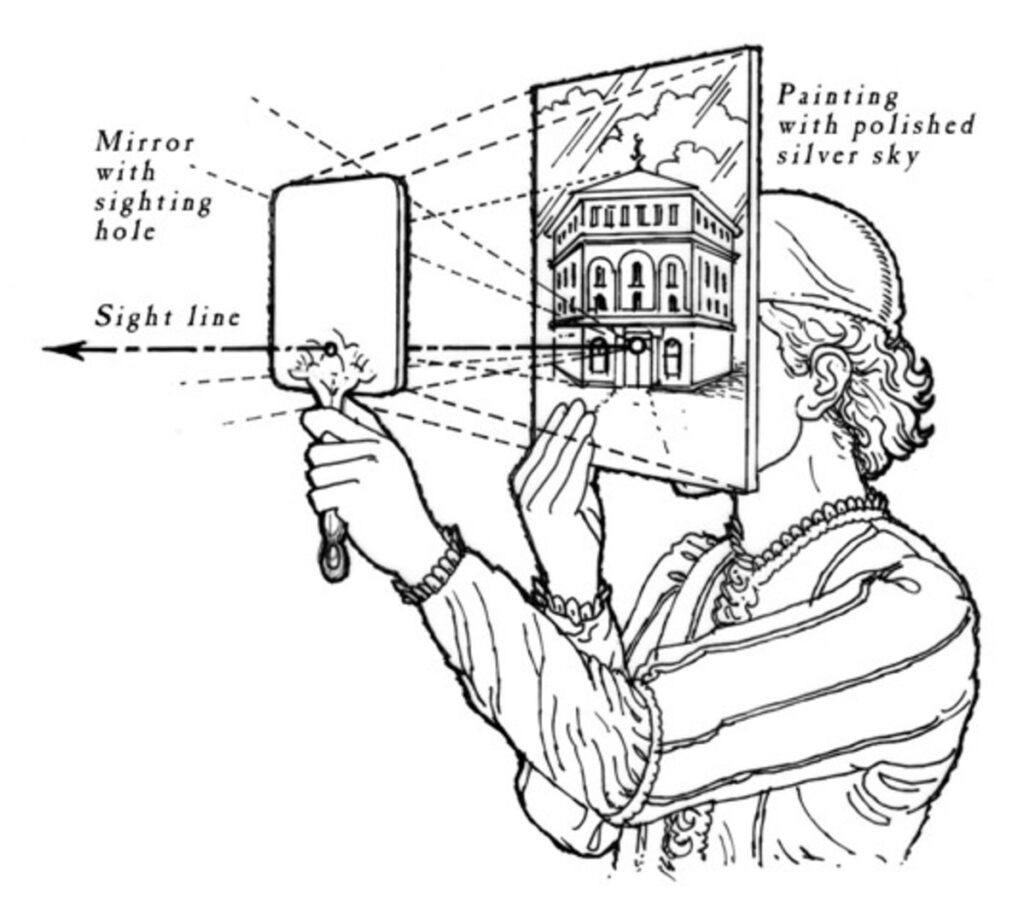

Experiments in the early 1400’s by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) produced a geometrical formula for 2 dimensional representation of perspective that became the standard model for the realistic depiction of space from the Renaissance onward.

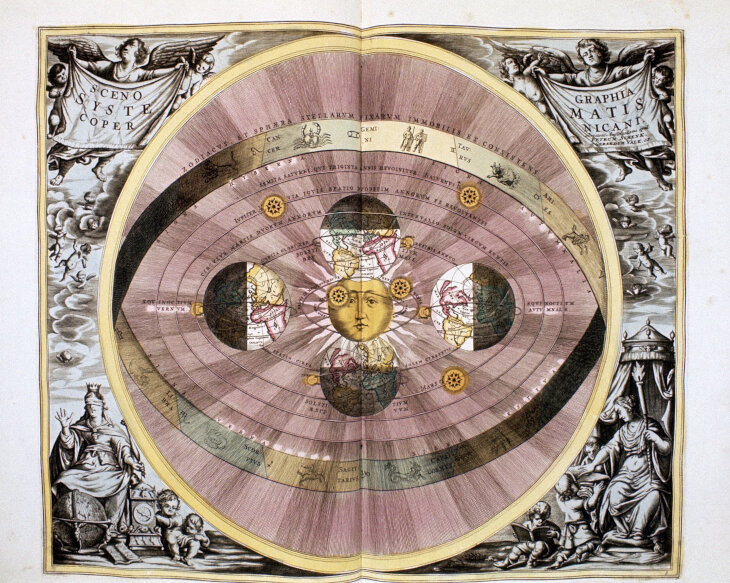

It was the development of calculus by Isaac Newton that gave the finishing touches to the Copernican heliocentric paradigm. It gave science a powerful set of predictive tools and emboldened man to believe that if these laws could be mastered the universe could be controlled.

With the earth removed from the center of the universe, the church lost its monopoly on science and art and so, armed an new mechanistic world view and with a powerful set of mathematical tools that seemed to have unlimited predictive powers, the western world entered what was called the Age of Enlightenment. This was an echo of the Renaissance and of the Golden Age of Pericles, during which Phidias worked. Culture was emboldened by this paradigm to believe in the perfection of mankind through accumulation of knowledge.

So we see that for each of these time periods the cultural understanding of mathematics had both direct and indirect relations to the culture’s self-expression, providing practical tools, useful paradigms and areas for further endeavor. What is the mathematical metaphor that dominates us in the information age? How does the math of today, and in particular Chaos Theory, in the early 21st century, reflect our cultural direction?

It should contextualize our work in history: It should provide a historical and geographical picture of cultural phenomena that is inclusive of the diversity of human experience. It should provide explanations for developments past and present and it should be able to identify current trends and predict future developments. It should make some sense of apparent paradoxes, contradictions and disparities.

It should give direction to movements or to individuals: It should provide motivation and direction to groups, individuals and specific works, just as ideals rooted in mathematics have, throughout the ages, inspired people to believe in the power of Art to elevate and enlighten.

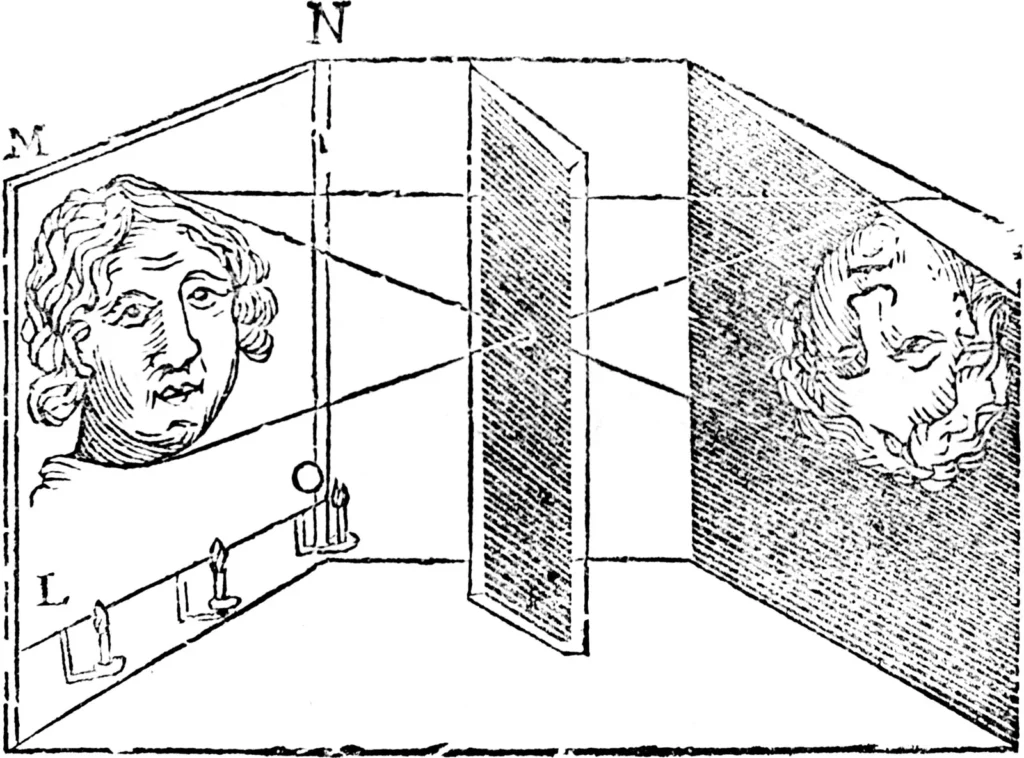

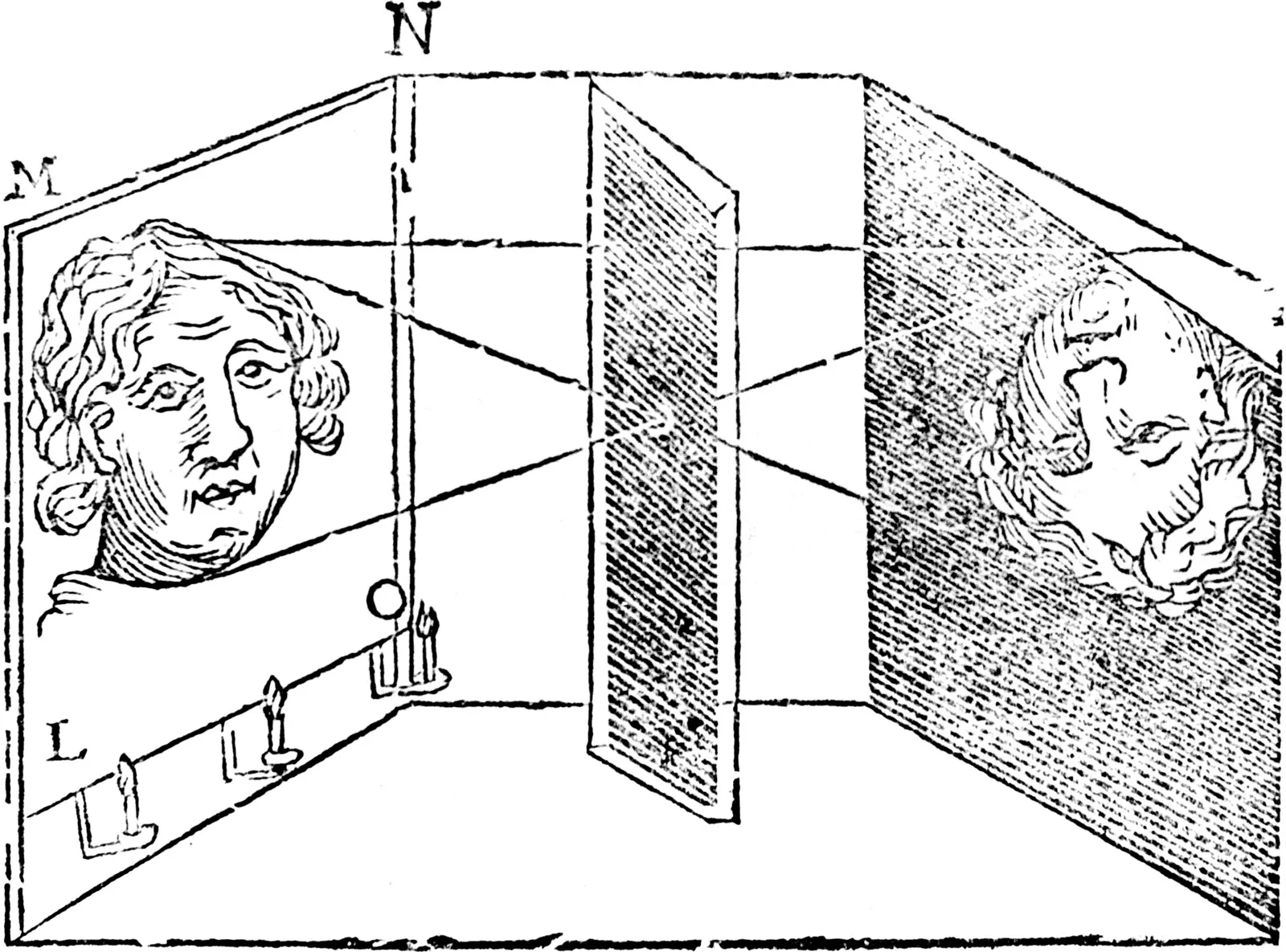

It should provide tools and technology: It should enhance or provide new avenues of expression and distribution. Just as the mathematics of optics provided optical devices that allowed painters to analyze what they saw and lead to the eventual development of the cameras and the scanners we use today.

It should provide metaphors and tools for critique and analysis: It should provide a language for understanding new concepts and relationships, just as the science of optics has given us the concepts of “focusing our attention” and “getting things in perspective”. It should also have the capability of self-analysis.

I propose that the study of complexity, also known as Chaos Theory can provide many concepts which help to give insight into the context and direction of contemporary culture, as well as technologies and methodologies for the production of valid work and theory. What tools can it provide us both practically and intellectually? Perhaps we should first ask what do we look for in such a paradigm.

A useful paradigm for artistic discourse should fulfill a few basic requirements:

It should open significant areas of endeavor: It should provide areas for artists and critics to direct their investigations and their works, in the same way that modernism opened the door to the study of contemporary life and ultimately art itself.keaways from your article, reinforcing the most important ideas discussed. Encourage readers to reflect on the insights shared, or offer actionable advice they can apply in their own lives. This is your chance to leave a lasting impression, so make sure your closing thoughts are impactful and memorable. A strong conclusion not only ties the article together but also inspires readers to engage further.

In the next installment I will propose how embracing Chaos can give us the tools and concepts to find meaning in the increasing Chaos of our world. Read More…

Leave a Reply